-- DRAFT PAGE --

Overview

Several rules can give fair shares of power to all voters setting budgets — just as there are several used for fair-share representation, and others to meet Condorcet's criterion. Each power-sharing rule for budgets meets basic goals for fairness and efficiency in different ways. But their differences are small compared to the change from winner-take-all to fair shares.

A big difference between BRV and VIP is the type of ballot. These offer tradeoffs between ease of voting or precise control of your spending.

Median Voter Process MVP the simplest system. Your ballot asks "How would you allocate the budget." The tally finds the median vote for each item, the one in the middle: half the voters want a smaller budget and half want a bigger budget.

MVP with Vote Trading A harder system starts with MVP but then lets voters trade votes, moving money on their ballots in exchange for someone else moving money on theirs. This is time consuming and the results are not very rational because many changes to the budgets depend on who is quickest to find a deal, not on any depth thinking about the effects.

Budget Refill Voting In BRV you give your biggest chips to the departments you think will make best use of the money. Then you can react to budget changes made by other reps by moving your own chips. The voters will most likely reach an equilibrium after several rounds.

BRV is easier than any method involving vote trading in the old smoke-filled back rooms.

Graded Ballots make BRV easier. You give your highest ranks or grades to the departments you think will make best use of the money. The tally program then gives your biggest chips to those departments.

Square-Root Voting asdf

The big money is here: in setting the annual budgets of large departments.

[ BRV2 will tell how BRV differs from MMV: 1) There are no free rides. The set of chips includes one chip for every column so the voter gives some money to every item, though some get more than others. While it is OK for an MMV voter to give nothing to a project someone else chose to fund; it is not OK to give nothing to an essential service. 2) There are no eliminations. 3) BRV replaces the rounds of MMV eliminations with rounds of re-voting, voters must personally react to changes. (The tally program cannot make this automatic without a very long ballot.) ]

All voting rules need accurate input to find the common good. They should motivate a voter to give his honest preferences, a "sincere ballot". The opposite, a "strategic ballot" is easy and tempting when setting budgets.

Giving all of your votes or money to your favorite is called dumping or a bullet vote. It is the first trick many voters try. So fair-share rules deter dumping by limit the maximum change a voter may push on a department.

Giving all of your votes or money to a handful of favorites is the next trick you might try. So fair-share rules encourage or force a voter spread out his money to many items.

The first trick many a voter thinks of is "move last." If other voters have funded his favorite, he does not need to give it any money; he give all his money to others he likes.

It is widely known that the best strategy for most point voting is to "dump" all of one's points on one's favorite. This is bad for decision making. It is not an accurate or sincere rating. It doesn't tell the community or the vote-counting rule how one feels about all of the other items. It rewards exaggeration.

A voter may try for a "free ride" -- even if dumping and bifurcating are impossible or unattractive,

- Make each voter stay within a limited budget and make the sum of all ballots stay within that limit.

- Limit each voter's minimum and maximum votes to avoid exaggerated and punishing votes. The limits can be hard barriers or soft incentives.

- Encourage or force the voter to spread out votes. Don't let them "bifurcate" by giving only minimum and maximum votes.

- Make time and incentives for discussion and negotiation.

The rules in this first section differ mainly in the ways they get voters to spread out their money. (The methods for spreading votes also determine whether the min. and max. votes are set by barriers or incentives.)

1) Personal scores by giving a personal score to each item. That will place the items in order and show how wide the gaps are between items. This is just like the scored ballot for selecting projects. And most people say it is too hard.

1) Smoothly spaced by chips whose values are preset by the people who choose the utility curve(s). The first round of voting uses the steepest line or curve; the last round uses a much flatter line or curve.

We hold at least two votes at [20]%. The second vote gives a voter the chance to counter surprising changes made by other voters. There might be a third or forth vote.

Advantages: Can be demonstrated on a tally board. Can use simple ballots with ranks or grades tallied by computer. This rule is the easiest for voters. It requires less time than other rules. There are few numbers to juggle or strategies to be troubled about.

Disadvantages: The voter may feel a lack of control; the min. and max. votes are ridged barriers.

If a computer "places" his chips he cannot precisely adjust the gaps between favorites. So his ballot might treat close favorites too evenly. Or a moderate who likes the current budgets might not want to give so much to his first choice and so little to his last choice.

Source: Similar rules have probably been used informally many times.

2) Progressive Influence Tax Influence on a budget means the percentage change from a neutral vote, that is a vote that makes no change. When a voter increases a budget, he pays some money to the tax; the bigger the change, the bigger his tax. His tax payment is divided among all other voters for the next round of voting.

Excel spreadsheet

Google Spreadsheet

Advantages: The more progressive the tax, the more it penalizes extream free-riding and dumping strategies. Yet it gives voters more flexiblity than chips with preset sizes. It also encourages vote trading.

It is simple enough to teach and tally with movable votes on table-top tally board. (The voter's first row of chips in a column is one chip deep. The voter's second chip in a column must be stacked two deep, one on top of the other. His third chip in the column would need two on top of it to pay his influence tax on pushing for a big change in the budget.)

Disadvantages:

Source: This is a simplified version of Hylland and Zeckhauser Influence Points.

3) Influence Points (square root of the influence points percentage change, not the square root of the budget) This charges the voter who changes a budget by taking some of his political influence points, not by taking some of his money.

Advantage: There is no wasted money and therefore less need for repeated rounds of voting.

Disadvantages: Each voter must keep track of two quantities that each limit his next vote: his stock of influence points and his unspent money.

Source: This is a modified version of Hylland and Zeckhauser Influence Points.

4) Normal bell-curve spread The voter has some freedom to vary the gaps between adjacent favorites. But his overall distribution is adjusted so its average is 0 (no change), its extremes are limited to about 3 and -3, and very little funding can reach those extremes. In fact, the more funding he moves toward the upper and lower limits, the more those limits move toward zero.

Advantages:

Disadvantages: The normal curve fits many patterns observed in nature: the height and weight of sixth graders, or of bananas. But there is no reason to suppose a rep's preferences on a particular ballot should fit this curve: strongly for one, luke warm or cool toward many, and strongly against one.

For most voters, the way each vote affects other votes is hard to understand. The ballot needs to be on a computer so a rep can see both her raw scores and her standardized scores. PoliticalSim offers players Standard Score voting on thermometer charts as a way of selecting the election rule.

It can not be taguht nor talied on a tally board.

Source: This is adapted from the Standard-Score rule for elections in Making Multi-candidate Elections More Democratic. by Samuel Merrill III, 1988.

A simple method of voting for budgets is shown in the Voting Workshop. This page builds on the workshop's budget-setting rule and shows how large groups can use it. It totally prevents exaggerated votes by limiting the voter to chips with preset sizes.

This rule can be tallied from preference ballots marked with ranks or grades -- the same sort of ballots used to elect candidates, enact policies, or select projects. Voters want simple ballots for easy voting, and simple tally methods for maximum transparency. As in Movable Money Votes for projects, the tally starts by giving big chips favorite departments and ends by giving small chips to the least favorite, lowest grade.

Voters use their chips to raise or lower budgets, and, as in any honest game, they must "lay their chips on the table" for everyone to see. This voting table is also a bar chart with columns for each department. Reps move their chips from one department's columns to another, causing or countering budget changes.

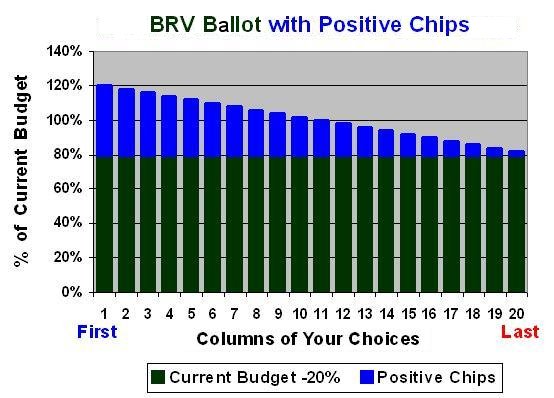

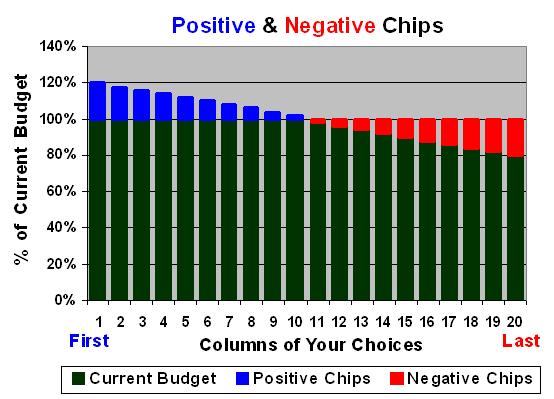

When a computer aids the tally, each voter gets many chips, as many as there are columns. The chips vary in value only a little from one to the next. So the voter cannot give exaggerated large or small amounts to favorites or foes. The tally automatically gives your largest chips to your favorite. And you may respond to budget changes by other voters by changing your ranks or grades.

The voting workshop introduced Budget Refill Voting which let a voter place her chips to cause budget changes, and then move them to counter budget changes by other voters. A small group with 10 to 50 voters could place chips on a tally board for 20 or 30 departments. They could then use the same process to allocate each department's budget among its bureaus.

Groups with more voters or departments, agencies, and bureaus need something else.

The chart below shows a voter's ballot adding chips to agency budgets. The first column of his favorite agency is the first column on the left. It gets his biggest blue chip. The agency at the middle gets a neutral vote, a vote that makes no change.

|

Accurate Democracy

Accurate Democracy