|

Different uses for voting

need different types of voting. |

|

Old Voting Rules for

|

|

|

Page in progress

|

|

Participatory Budgeting (PB) is a big step forward for democracy. So there's no wonder why it is spreading so fast. But it is spreading largely by word of mouth and local news stories. So it has been rather slow at jumping from Latin America to English-speaking North America.

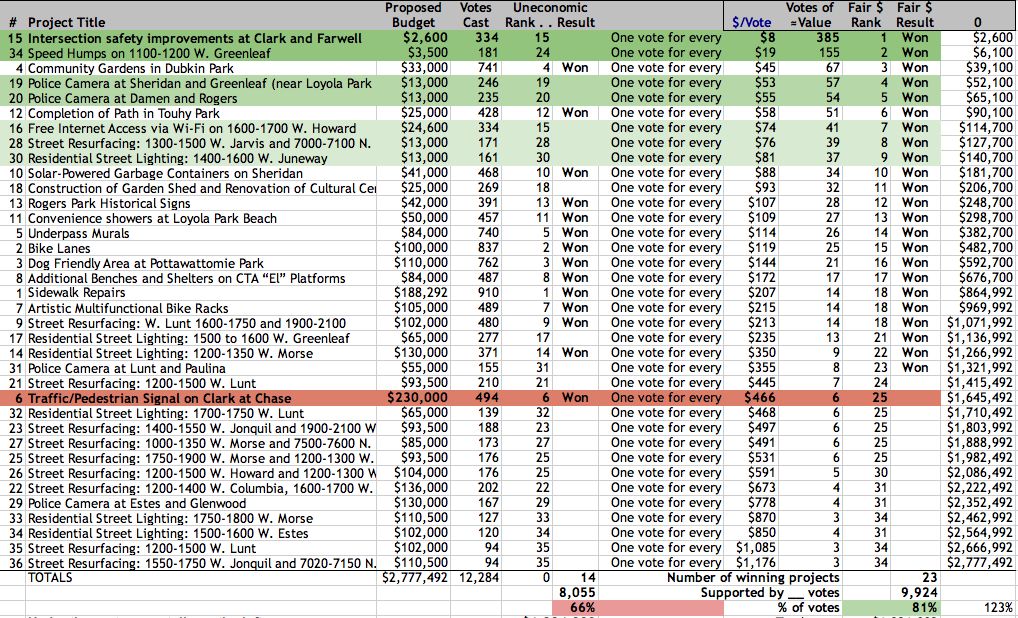

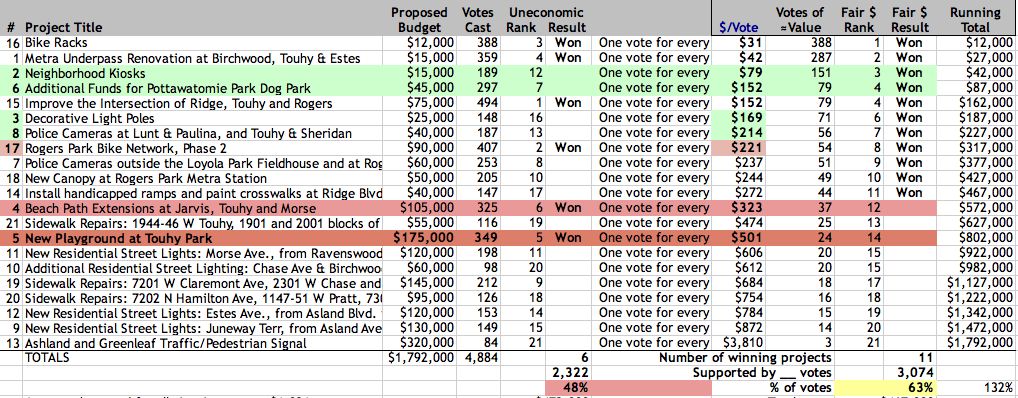

Even the most basic PB is better than top-down control of all funding. But there are strong rewards for making the process and the results as efficient as practical. To do that, we need constructive criticism, looking at some cases with the goal of making them better. This page looks at the last step in the PB decision process: voting to choose the winning proposals. Why use better voting methods in PBFewer wasted votes; more happy voters; more support for the process. More useful winners; more cost-effective winners; better use of the money. Fair to each proposal and its supporters; fair to minority interest groups; equal money value for each vote and each voter. Less need and chance to “game the system” with strategic nominations and tactical voting. Examples of the need for fair-share fundingParticipatory Budgeting in Twin Oaks, Virginia, 2008In the late 1990s, electric carts were proposed to aid elderly and injured members. This was a very high priority for some older members, but some younger ones thought it was a luxury that would reduce healthy exercise.Most of the voters were not elderly, injured or disabled. They were empathetic, but they did not give a high priority to some things the old folks wanted. So the electric carts were delayed by the old voting scheme, which did not give a large minority the power to fund its own needs. After a few years, the elders convinced many younger members to vote for this priority. But the community came to see that the only way to let all groups meet their own needs is through some kind of fair-share voting to allocate some money and labor hours. The people who developed Fair Share Voting (FSV) have used PB in one small community since the mid seventies and have worked on MMV since the mid nineties. We want to give constructive criticism to help the PB process improve and spread. Better that such criticism comes from us than from those who want only central control of public funds. All of the developers have worked on other social change campaigns. We know well the need to keep the changes simple in order to win. Higher goals can come later. But they should not be delayed too long. We must have better methods ready in case the first very simple one fails to satisfy some groups of voters or is attacked for its failings. The voting at Twin Oaks is part of a months-long process called the “Trade-Off Game.”  Participatory Budgeting in Chicago's 49th Ward, 2010The recent PB votes in Chicago can be educational. Some people in the PB movement try to help each community choose its own voting method. This cannot be done quickly in cities where people have used only one kind of voting: plurality rules. They do not know the qualities of other methods. Values of votes in 2010$1,324,000 was available.

A voter could cast up to 8 votes on a ballot — but could give only 1 vote to a project. No Cumulative Voting was allowed. Under the tally on the left, which is unconcerned with costs, 14 projects won. Under the cost-aware tally on the right, only the most expensive of those winners would have lost. Ten cost-efficient projects would take its place. |

|

Under the cost-aware tally on the right, only the most expensive winner would have lost. Ten cost-efficient projects would take its place.

(It is possible but not likely that 342 voters happened to cast all 2,363 votes for the 10 projects which replace the 1 costly project.) We could say the cost-aware or fair-$ result beats the uneconomic result by 9,924 votes to 8,055 votes. That is 1,869 more votes or 23 percent more. Better voting rules such as MMV would give even better results because they leave fewer wasted votes. Changing the voting rules from year to year lets different interest groups have a chance. Both Twin Oaks and the 49th Ward have done this. It may be a small burden for voters to learn a new wrinkle each year, but it also makes voting day more of a game and a celebration. The 2010 tally shows why voting that is cost unconscious is bad: It lets a costly project eat up the funds and leave many popular projects empty. The 49th Ward's website explained: “Though most neighborhood residents support the participatory budgeting process, many expressed concern that traditional "nuts and bolts" infrastructure improvements, such as street resurfacing, may not have received the attention and funding they deserved. Of the seven street resurfacing proposals on the ballot, only one garnered enough votes to receive funding out of the 2010 aldermanic menu. This is likely because most of the winning proposals, such as artistic murals and dog friendly areas, had a ward-wide constituency, whereas the constituency for a specific street resurfacing proposal is limited to those who live on or use that street.” “Most of the residential streets in the 49th Ward were last resurfaced in the late 1990s and are beginning to show their wear. Though most residents agree that our residential streets deserve attention, the participatory budgeting vote process was set up in a way that may have unintentionally shortchanged block-specific proposals.” The falsely simplistic voting system used in 2010 needed improvement, according to some people. So the leaders decided to give street resurfacing a separate ballot question which they placed above all other kinds of projects; then it was tallied and funded before all other projects. That took some power away from the voters. And it still did not solve the problem of how to fund groups with needs that do not get wide attention. Next, the 2011 tally will show expensive projects again plus other major flaws: privileged projects (the street resurfacing) and “wasted votes”. All of those are avoided by the fair-share voting rules in this chapter.  Participatory Budgeting in Chicago's 49th Ward, 2011Values of votes in 2011$480,000 was available.

A voter could cast up to 6 votes on a ballot – but could give only 1 vote to a project. No Cumulative Voting was allowed. Even the winning votes were wildly unequal !

|

|

Losers 2, 3, 6 or 8 were each more cost effective at getting votes than winners 4, 5 or 17.

If we combine projects 2 and 6, we might get a project worth 486 votes for $60,000.* According to voters, this is a much better use of money than project 5. * But a voter who had voted for both is not allowed to give 2 votes to the new proposal. The dog park proposal (#6) might add a neighborhood kiosk (#2) and decorative light poles (#3). These might attract the throw-away sixth votes of people whose real desire is for the neighborhood kiosks and decorative poles. Under the old voting rule, the added cost does not count against the expanded proposal. If we combine projects 2, 3 and 6, we might get a project worth 634 votes for $85,000.*

Fair-share tallies with transferable votes solve all of these problems, as explained below. In a separate section, Chicago's 2011 PB ballot used averaging of the dollar amounts voted for street resurfacing.

Better PB Voting Steps ForwardParticipatory Budgeting is a big improvement over the old ways to identify, develop and select local projects worth funding. The Chicago results would have been even better if the same ballots went through a cost-aware tally. That is the first of several steps toward the really efficient use of money that we can get from fair-share voting. The steps are simple. Each step is a clear improvement over the previous voting method. Bloc Voting gives each voter as many votes as there are seats to fill, or projects that we can afford. It elects the candidates which get the most votes. It is a majority rule: The majority can win all of the seats — if they do not divide their votes among too many candidates. The 2011 PB vote in Chicago was like Bloc Voting: Voters got 6 votes and as it happened, 6 projects won. Limited Voting gives voters fewer votes, for example, 3 votes for an election to fill 5 seats. It is a semi-proportional rule: It gives the majority a majority of the seats and the minority a chance to win a share of the seats — if each group does not divide their votes among too many candidates. The 2010 PB vote in Chicago resembled Limited Voting: Voters got 8 votes and 14 projects won funding. A common problem in plurality rules is that having too many nominees divides an interest group so they get less than their fair share of winners. In this situation, groups make “back-room deals” to avoid getting too many nominees. Each back-room deal leaves most people out of the real decision; their votes merely rubber stamp it. But PB voting adds another major problem: Winning costly projects can give a majority or minority far more than its share of funding. Which leads us to the next step needed for fair share voting for budgets. A Cost-Aware Tally elects the projects which get the most votes compared to their costs. It can use ballots from Bloc or Limited Voting. This tends to elect many low-cost winners rather than a few high-cost winners. Cost-aware results always beat the uneconomic results:

We would predict that ballots from the 2010 PB vote would show fairness is improved by a Cost-Aware Tally. (That means the allocations attributable to each ballot will be more equal as measured by a Gini index.) Unfairness is bad in itself and is a sign of poor utility value for the average voter. But a cost-aware tally makes it harder for a costly project to win. Cumulative Voting is then needed to give a costly project a fair chance: The rules should let a voter give it more than one vote. And that is what Cumulative Voting can do. For example, it may let a voter give 1 vote for each $20,000 in the project's cost. Assisted Cumulative Voting (ACV) eliminates the weakest project with the fewest votes per dollar. But it does not “waste” those votes; it transfers them. When it transfers your vote(s) from a loser, ACV does not change each remaining project's relative share of your votes. (Perhaps you gave a loser 3 votes and a couple other projects 1 vote and 2 votes. When ACV transfers your 3 votes from the loser, it gives your remaining projects 2 votes and 4 votes.) A group with too many projects will see votes for their weak projects transfer to help elect their strong ones. We can't afford everything; so some projects must lose. But that does not mean some voters must lose their votes. Benefits: ACV would lead to fewer wasted votes, higher fairness and thus higher utility and voter satisfaction with the winners. But we invented ACV only as a step to help teach the best voting method. ACV cannot efficiently transfer excess votes from a winner which has more than enough, i.e. the number of votes it needs in order to win. Transferring excess votes could cause a project to give away the very vote(s) it must have to remain a winner later in the tally. To transfer excess votes well, the voting method needs to set a “threshold of victory” or quota. With this step we arrive at a method like the Single Transferable Vote. Also some PB elections have proposals with low costs relative to the money per voter. Then PB needs to make each project prove it is an important public good by winning funding from a substantial fraction of the voters. We should set this quota before the election. With this last step, we arrive at Fair Share Voting (FS). It lets a voter fund only a set fraction of each favorite project. So to win its funding, a project needs support from a large number or quota of voters. This tally that lets each voter allocate only a fair share is inherently cost aware. You rank your favorites. The tally distributes your share to as many of them as you can afford to help fund. And a tally of all ballots drops the least-funded project. This repeats until all projects still in the race are fully funded. This section on “Better PB Voting Steps Forward” is formatted as a pdf for printing. The Chicago PB tables for 2010 and 2011 also are formatted in a pdf.

Any PB voting that is fair share offers a big improvement over wasteful unfair methods. Fair-share voting can reach even better results with steps explained on other pages in this chapter. The next page looks at notes about fair-shares. |

|

|

Participatory Budgeting in

Participatory Budgeting in  Participatory Budgeting in

Participatory Budgeting in

Accurate Democracy

Accurate Democracy